A New Measure of Feeling Safe: Developing Psychometric Properties of the Neuroception of Psychological Safety Scale (NPSS)

Liza Morton served as lead for writing—original draft and contributed equally to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, and visualization.

Nicola Cogan contributed equally to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, and writing—review and editing. Jakec Kolacz contributed equally to formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, software, supervision, visualization, and writing—review and editing and served in a supporting role for conceptualization. Calum Calderwood contributed equally to data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, and writing—review and editing. Marek Nikolic contributed equally to data curation, formal analysis, validation, and writing—review and editing and served in a supporting role for methodology. Thomas Bacon served in a supporting role for conceptualization and writing—review and editing. Emily Pathe served in a supporting role for conceptualization and writing—review and editing. Damien Williams contributed equally to supervision and served in a supporting role for conceptualization. Stephen W. Porges contributed equally to conceptualization, methodology, validation, visuali-zation, and writing—review and editing. We have no known conflicts of interest. Jakec Kolacz’s and Stephen W. Porges’ work on this project was supported by gifts from the Dillon Fund, the United States Association for Body Psychotherapy (USABP), and the Chaja Foundation. Anonymized data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Liza Morton, who is now at the Department of Psychology, Glasgow Caledonian University, Cowcaddens Road, Glasgow G4 0BA, Scotland, United Kingdom. Email: liza.Morton@gcu.ac.uk

Psychological safety is recognized as central to mental health, wellbeing (Sullivan et al., 2018) and posttraumatic growth (Nor-man et al., 2020) with increasing clinical interest and research attention toward its importance. Feeling safe is recognized as a distinct state important for rest, restoration and social bonding (Porges, 2011). As social beings perceived threat is often interper-sonal while safety with other people is communicated using com-passion (Gilbert, 2017). Compassionate interventions, such as the use of soothing voice tones and breathing, reduce the fight/flight response, decelerate heartbeat and facilitate parasympathetic rest and restoration (Kirby et al., 2017). A safe and compassionate early environment shapes the nervous system and aids the devel-opment of self-soothing strategies that enable self-regulation in later life (Gilbert, 2017). Trauma symptoms arise from unregu-lated threat preoccupation, when self-regulation is not available, which affects our biology, social interaction, and maturation (Mot-san et al., 2021; van der Kolk, 1994).

To date, psychological safety research has largely been considered within organizational and group contexts, describing the process of assessing risk in interpersonal relationships and occupational envi-ronments. The Team Psychological Safety Scale (Edmondson, 1999) is a 7-item self-report scale that measures perceptions of feeling safe within teams which has good reliability and validity (Ming et al., 2015). Increased sense of psychological safety at work facilitates em-ployee communication, improvements in learning, teamwork and work performance (Edmondson & Lei, 2014; O’Donovan et al., 2020). The positive impact of psychological safety has been found in other organizational contexts, including public spaces, education (Wanless, 2016), community building (Singh et al., 2018), and com-municating in medical teams (Real et al., 2021) and in health care workplaces to reduce levels of psychological distress and trauma (Ahmed et al., 2021). However, psychological safety and its mea-surement differs within teams differs from the individual.

Psychological safety for the individual, rather than within teams, has also begun to gain attention within mental health set-tings regarding clinical understanding of trauma related conditions and trauma informed practices (Isobel et al., 2020) where tradi-tional measures focus on pathology rather than prevention and positive adaptation. Difficulty in assessing danger or safety and modulating fear response is reported in individuals suffering Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD; Jovanovic et al., 2012). A novel manualized cognitive-behavioural treatment for PTSD called ‘Seeking Safety’ which prioritizes feeling safe (Najavitis, 2001) delivered improved outcomes in symptoms of PTSD and psychiat-ric distress compared to controls (Desai et al., 2008). ‘The Feeling Safe Program’ aims to address safety feelings when treating perse-cutory delusions in psychosis and a clinical trial of this interven-tion showed recovery (Freeman et al., 2016).

The following psychological scales include a component of psy-chological safety. In the Activation and Safe/Content Affect Scale (Gilbert et al., 2008) safe affect is shown to negatively correlate with measures of depression, anxiety, stress, self-criticism, and insecure attachment. The same research team developed the Scale of Childhood Memories of Emotional Warmth and Safety (Richter et al., 2009). The Therapeutic Environment Scale includes a ‘feel-ing safe with others’ subscale, validated using clinical samples (Veale et al., 2016). The Child Safety Behavior Scale has been developed to measure safety-seeking behaviors (Alberici et al., 2018) but is less concerned with affective states. In medical settings concern for the sense of safety experienced by patients (Ellegaard et al., 2020; Morton, 2020) and when exposed to disempowering aspects of care (Morton et al., 2020)is of interest in terms of quality of experience and speed of recovery. In one study, feeling safe during the process of hospitalization was found to increase feelings of control, calm and hope (Mollon, 2014). Feeling safe has also been found to improve healing and re-covery during maternity care of women who have experienced childhood sexual trauma, while feeling unsafe with professionals could be experienced as retraumatization (Morton, 2020).

In sum, to date psychometric measures of feeling safe have been restricted to specialized contexts such as team safety (Edmondson, 1999) childhood memory of safety (Richter et al., 2009), as a subscale (Veale et al., 2016), or as a dimension of a broader scale under factor analysis (Gilbert et al., 2008) rather than the central construct. Due to the importance of safety within a therapeutic context and the lack of a general dedicated means of measurement that considers relationship dynamics (Roussin et al., 2016), there is a need for the development of a refined psychomet-rically validated scale of psychological safety.

The Polyvagal Theory (PVT) offers a comprehensive explana-tion of psychological safety grounded in an evidence-base of neu-rophysiology, psychology and evolutionary theory. PVT describes how situations are subconsciously assessed for safety or threat by the autonomic nervous system, termed “neuroception,” leading to corresponding physiological, affective, and behavioral responses (Porges, 2004). In developing a scale of psychological safety, PVT proposes that situations detected via ‘neuroception’ as safe will activate physiological, affective, and cognitive processes to optimize social engagement through compassion for others. Situa-tions detected as unsafe will shift bio-behavioural systems that would restrict interpersonal social engagement, while optimizing physiological state, via the autonomic nervous system to support defensive survival strategies either via the dorsal vagal pathway leading to immobilizing, death feigning, or dissociating or via the sympathetic system leading to fight/flight behaviors that would be supported by increases in heart rate, shortened breathing, and increased muscle tension (Kolacz et al., 2019).

PVT has helped to inform mental health, medical, and educa-tional practices in the use of safe therapeutic presence (Geller & Porges, 2014), recognition of client’s nonverbal safety-signaling (Mair, 2021) and interpreting representations of fear and safety in art therapy (Gerge, 2017). It has also acted as the basis of the Body Perception Questionnaire (Cabrera et al., 2018) and the Brain-Body Center Sensory Scales (Kolacz et al., 2018) support-ing the utility of PVT as the grounding for a new general scale of safety. As such, the current study aimed to develop such a self-report measure, the Neuroception of Psychological Safety Scale (NPSS) informed by the PVT (Porges, 2004, 2011, 2021

Method

Ethics

Ethical approval for this research was sought and received from the University Ethics Committee and all participants provided informed consent to their participation prior to engaging with the research. All participants were recruited using convenience sampling using online platforms, Facebook, Twitter as well as university recruitment posters.

Phase 1: Development of Statement Items

Item development for this study followed the best practices for domain identification, item generation, and theoretical analysis (Boateng et al., 2018). A variation of the e-Delphi methodology was employed to facilitate the first phase of the process (Skul-moski et al., 2007).

Six international experts in the PVT, Clinical and Counseling Psychologists, and therapists, with academic and clinical experi-ence in trauma work, were identified. These experts were recruited to include leading expertise in the PVT (SP, founder of the PVT; Deb Dana, Psychotherapist, founding member of the Polyvagal Institute and leader in PVT informed therapies; JK), development of PVT-informed psychometric measurement (JK), and clinical and academic expertise in trauma (NC, Consultant Clinical Psy-chologist/Senior Lecturer; LM, Counseling Psychologist/Lecturer; EP, Counseling Psychologist/Lecturer; TB, Consultant Clinical Psychologist).

Applying the e-Delphi method (Skulmoski et al., 2007) the stakeholders first agreed on the aims of the study which were to generate a consensus on a list of items pertaining to psychological safety. To generate items each expert stakeholder anonymously provided items pertaining to what it means to feel safe via e-mail. Specifically, in the first round an open-ended questionnaire asking ‘What does it means to feel safe?’ was used to systematically solicit and collect items from all stakeholders, anonymously and individually, via e-mail to the lead author (LM). Following this item generation, these items were collated by the lead author who redistributed the complete list via e-mail to each of the key stake-holders inviting feedback and critique and the opportunity to reevaluate their initial responses. Subsequently, there was a pro-cess of combining and redistributing the items until a consensus over a final set of items was reached by all stakeholders. Following four rounds 107 items were agreed by all stakeholders.

Phase 2: Item Reduction and Piloting

The second phase of developing the NPSS involved piloting the items generated in Phase 1 to reduce the number of items and to ensure that the questions were relevant clear, and measured what they were intended to measure (Boateng et al., 2018).

Procedure

First, this was achieved through assessing the 107-item NPSS and removing items that did not contribute to the measure using stakeholder review and exploring the factor loadings of the state-ment items. The 107 items formed the basis of the piloting of NPSS. The stimulus for the NPSS used to evaluate the items was “Think about a recent specific situation when you felt safe, and please rate the following statement items in relation to this.” The final set of the items was randomized in accordance with a five-point Likert scale, with lower scores indicating less agreement with the item for example, Strongly Disagree (score = 1), Dis-agree (score = 2), Neither Agree or Disagree (score = 3), Agree (score = 4), Strongly Agree (score = 5). Two other options were added Prefer not to say and Not applicable. Collected data were treated as ordinal as appropriate of data regarding attitudes (Hair et al., 2019). Statistical analyses were conducted with RStudio software for Windows, Version 1.2.5019 (RStudio, 2009–2016), and IBM SPSS (IBM Corp., 2017). Factor analysis was completed employing the fa function included in Psych package for R (Rev-elle, 2017).

Exploratory Factor Analysis

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of the NPSS was con-ducted to examine the factor structure and reduce items. The ex-ploratory factor retention was guided by factor loading, theoretical predictions, scree plots, and model fit. The goodness of fit to the data was evaluated by using the root mean squared error of approximation (Steiger, 1990), Tucker-Lewis index (Tucker & Lewis, 1973), and the Comparative Fit Index (Bentler, 1990). Eigenvalues were observed for the last considerable drop in magnitude. The factor analysis was subject to oblimin rota-tion; factors related to safety were expected to correlate and not to be highly complex (Fabrigar et al., 1999). Factoring method by minimal residuals was used (minres), discussed to be optimal for oblique data (Brown, 2009). Internal reliability was assessed using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients with the threshold for acceptability at .7 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). In support, Omega h was calculated to assess the lowest level of reliability to multiple latent factors. Dunn et al. (2014) summarize the advantages of omega over alpha. Only items loading . .6 were retained unless cross-loaded with another factor ..45 (Ladhari, 2010).

Results

342 participants consented to and completed the NPSS. Data were accepted for inclusion if most of the NPSS was completed and participants did not fail attention checks. Six participants were excluded based on failing attention checks. Attention checks required participants to provide a specific answer (e.g., “Please, select Not-applicable”). The final number of responses for analysis was 336 (229 women, 103 men, 4 nonbinary). The mean age of participants was 32.87 (SD = 12.17, range = 54). Ethnicity was predominantly given as white Scottish.

Missing data were deleted pairwise, so if a participant com-pleted most but not all the NPSS, their answers were included in the analysis. A correlation matrix was calculated. A single mea-sure of correlation strength was obtained by calculating a back-transformed mean Fisherman Z score for each item (Salkind, 2013). 33 items were removed prior to factor analysis for the fol-lowing reasons: 1. Duplicate items and very similar items were reduced to a single item. Correlations among the pairs and groups of similar items were explored. If their face similarity was sup-ported by correlation ..7, only the highest correlating item remained. 2. Items that correlated poorly with all other items were deleted. The final number of items evaluated in the EFA was 74.

Factor Structure of the NPSS

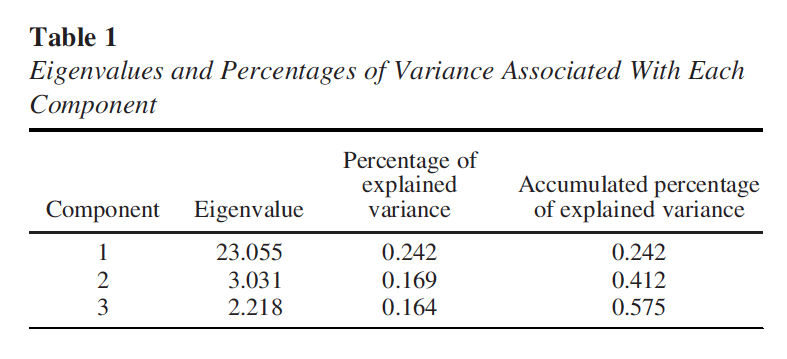

Polychoric correlations were calculated and a polychoric paral-lel analysis was employed to explore the factor structure as appro-priate for ordinal data (Garrido et al., 2013). Decisions for factor retention were guided by a combination of absolute fit indices, scree plot, and simple structure (Fabrigar et al., 1999; Montoya & Edwards, 2021). The NPSS scree plot and goodness of fit indices did not provide a clear solution on the first iteration. Visual examination of the scree plot (see supplementary materials) indicated one large eigenvalue fol-lowed by relatively small values without a clear second drop, indicating a 1-factor solution. One factor solution was not sup-ported by model fit statistics (RMSEA = .093 [90% CI: .091– .095], CFI = .63, TLI = .62). On second iteration, items that did not load substantially on any factor were dropped. The resulting pool was reanalyzed. The visual analysis of the screeplot B showed three deviating eigenvalues suggesting a 3-factor model to explain the data (Table 1). All items demonstrated simple struc-ture by loading substantially on only 1 factor, thus we accepted the 3-factor solution (RMSEA = .083 [90% CI: .080, .086], CFI = .80, TLI = .78).

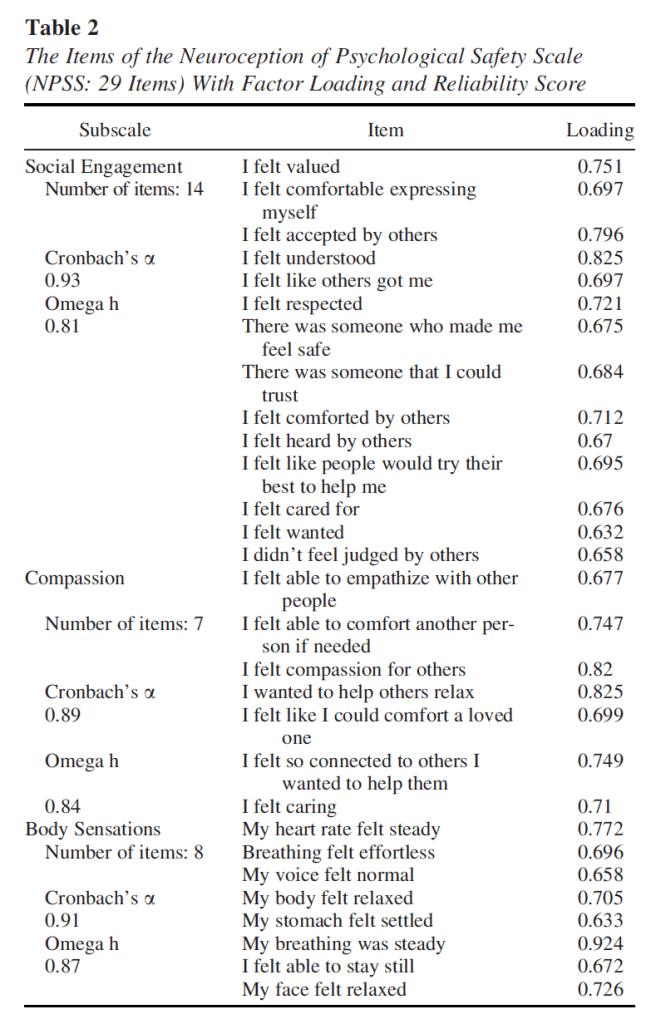

Bartlett’s test of Sphericity indicated a good factorability (v2 =398.96;df = 73; p , .01–13)ofthecorrelation matrix. The correlations between the factors were moderate; between the first- and the second-factor r = .65, between the first- and third-factor r = .52, and between the second- and third-factor r = .50. Factor loading thresholds of loading ..6 were applied (Wolfinbarger & Gilly, 2003). The resulting factors corre-sponded with the theoretical concepts of safety; Compassion, Social Engagement and Bodily Sensations. All items within a factor conceptually coalesce. Items demonstrated a simple structure, and none of the items cross-loaded substantially on more than 1 factor. Resulting items and factor loadings are pre-sented in Table 2. Cronbach’salpha and Omega h were calcu-lated for each subscale separately.

Internal Consistency

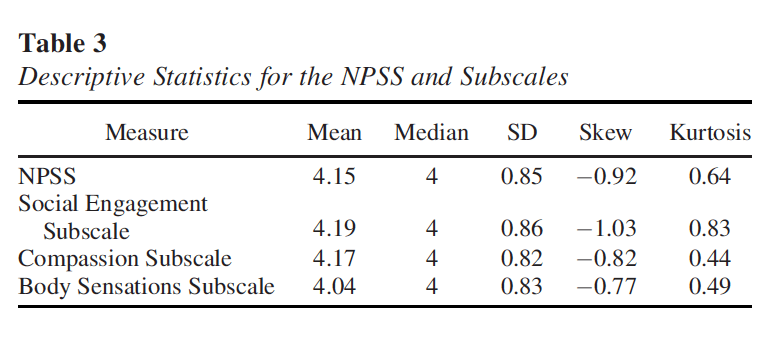

Descriptive statistics for NPSS are presented in Table 3.The NPSS deviated from normality as assessed by skewness, kurtosis, and Sha-piro-Wilk tests (p , .05). Reliability measures used do not rely on nor-mality assumptions. Internal consistency was assessed by Cronbach’s alpha and omega hierarchical coefficient. Cronbach’salphahasbeen shown robust to nonnormally distributed data when the dataset is suffi-ciently large, but it can be affected by test score distributions (Sheng & Sheng, 2012). Omega hierarchical, implemented in the Psych R pack-age (Revelle, 2009) provides superior internal consistency assessment when data are ordinal. Omega h scores range from 0–1, appropriate values for psychometrically evaluated scales ranged from .6 to .98 (Viladrich et al., 2017).

Post Hoc Analysis

As described the resulting factors corresponded with the theo-retical concepts of safety; Compassion, Social Engagement and Bodily Sensations which were considered subscales. A total score of each subscale was calculated for each participant to analyze the difference between genders (Norman et al., 2020). Independent sample t test revealed that there was no significant difference between genders on Social Engagement and Compassion sub-scales. Males (n = 92, M = 31.74, SD = 5.54) had significant lower scores than females (n = 217, M = 33.2581,SD= 4.36) on the Body Sensations subscale after correction for unequal variances (t [140.9] = 2.340, p = .021, Cohen’s d = .3, equal variances not assumed). Similar results were obtained after 1000 bootstrap sam-ples (p = .026) to control for unequal sample sizes.

Phase 3: Internal Reliability and Dimensionality

Procedure

The third phase involved administering the 29-item version of the NPSS to a sample of participants using the same inclusion cri-teria and procedure as in phase 2. The aim was to assess the inter-nal reliability and dimensionality of the NPSS. Participants were invited to complete the 29 item NPSS. Five demographic ques-tions were included; gender, age, ethnicity, country of residence and working status. The present study utilized a survey design for the purpose of psychometric evaluation. In tests of dimensionality and reliability, the NPSS was independently assessed at item-level. Monitoring of data part-way through collection revealed a low male response rate. Targeted recruitment on aforementioned social media sites was conducted using an updated recruitment poster. A total 455 participants completed the survey. Excluding participants who did not fill the NPSS and standardized measures or otherwise showed excessive or nonrandom missingness on these measures, this number was reduced to 318 (86 males, 5 nonbinary or not-sure). The mean age of participants was 22.66 (SD = 14.65, range = 18–71). Ethnicity was predominantly given as white Scottish.

Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using RStudio software for Windows, Version 1.3.1093 (RStudio inc., 2009–2020). In order to maximize available data and reduce biased estimates, an im-putation method was applied to missing item data. As data appeared to be missing at random and rates of missingness were low (1.13%) a single imputation method was deemed appropriate (Dong & Peng, 2013). This was conducted using the expecta-tion-maximization algorithm. Descriptive statistics for the NPSS were generated, giving indications of normality and potential outliers. A content analysis was conducted for answers to the NPSS open-ended stimulus-prompt question, uncovering themes and frequency of their occurrence in participant-generated situa-tional stimuli. Dimensionality of the NPSS was measured using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), with predicted factors based on an exploratory factor analysis conducted during the first phase. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to determine internal reliability of the scale and subscales in the NPSS. While Cron-bach’s alpha is a standard test of reliability, it has been found to show bias for scales that are not unidimensional or that do not show tau-equivalence, and so McDonald’s Omega was also conducted to triangulate results (Trizano-Hermosilla et al., 2016). Sum scores of the NPSS were calculated and used in validity testing. Known groups validity was investigated via an independent t-test comparison of men and women’s NPSS scores, predicting significantly lower results for women in line with published liter-ature (Logan & Walker, 2021).

Results

Initial data exploration uncovered a sum score mean of 119.48,(SD = 14.85) and item mean of 4.12. Negative skew ( .97) and positive kurtosis (3.75) were found in NPSS sum scores. A mean-ingful pattern in low-scoring outliers of the NPSS was also identi-fied. In answer to the situational prompt open-ended question, these individuals chose asocial situations such as being home alone, unlike the majority of participants who chose a social situa-tion. Removal of outliers showed no change in nonnormality and so were included in dimensionality and reliability testing. Outliers were deleted from correlation and regression analysis however, as these tests are sensitive to the presence of outliers and may also lead to reduced linearity of variables (Wilcox, 2016).

Open-Ended Question Content Analysis

A total 86 responses were given for the open-ended situational prompt question. A conceptual content analysis revealed that 58 (67.44%) chose interpersonal situations involving loved ones, friends, colleagues or caring professionals. Only 3 (3.48%) chose explicitly asocial situations, while the remainder focused on loca-tion, situation or material safety (such as being at home or at work).

Dimensionality

The data were assessed for multivariate normality using Mar-dia’s test. Due to failure of testing, factor analysis results are reported with robust standard errors and Satorra-Bentler correc-tions. Fit indices show that the proposed 3-factor model met rec-ommended cutoff levels of good fit for v2 (difference v2 = 772.44, df = 374, p , .001), RMSEA (.058) and SRMR (.062), while CFI (.86) and TLI (.84) closely approached cutoff levels (Hu & Ben-tler, 1999). Factor loadings show acceptable fit of items to the three factors, however question 1 ‘I felt valued’,2‘I felt comforta-ble expressing myself’ and 14 ‘I didn’t feel judged by others’ did not meet stricter standardized loading cutoffs of # .7 (MacCallum et al., 2001).

Internal Reliability

Cronbach’s alpha for the entire NPSS was .95. Subscale results were .93 for social engagement, .94 for compassion and .92 for bodily sensations, suggesting good internal reliability of the scale and subscales (Agbo, 2010). In all cases, a could not be increased by excluding items. Omega h total scores were .96 for overall NPSS, .93 for social engagement, .93 for compassion and .92 for bodily sensations, confirming the findings of Cronbach’s alpha testing (McNeish, 2018).

Discussion

The study reports that the NPSS is a psychometrically sound measure that captures the multiple dimensions of psychological safety that people experience but that, until now, have been diffi-cult to operationalize and measure. The first phase resulted in gen-eration of 107 items pertaining to what it means to feel safe by psychologists and researchers with expertise in trauma and the PVT creating the comprehensive NPSS. The second phase evaluated the items and assessed factor structure, thus creating the 27-item NPSS scale with three subscales consistent with understanding of safety as proposed by the PVT and literature in psychological safety. The first factor, termed Social Engagement, is characterized by being accepted, understood, cared for, being able to express oneself with-out being judged, and having someone to trust. The items indicated evaluation of the social environment as nonthreatening and safe to engage socially—a property ascribed to the Social Engagement System (SES; Porges, 2011). The second factor captured items related to the ability to be compassionate and feeling connected, empathetic, caring and wanting to help. Being compassionate regulates our autonomic nervous system (Kirby et al., 2017) while regulation occurs through the ability to self-soothe (Mok et al., 2019) and communicating safety. In therapy, compassion is increasingly seen as central to promote safety and develop/reengage self-soothing strategies (Gilbert, 2017). The third fac-tor related to the internal sensations of the body in a state of calm capturing the feeling of relaxation in the face and the body, steady heartbeat and breath, and settled stomach. The activation and functioning of the SES are associated with the regulatory function, especially of the heart and bronchi and the associated state of relaxation and restoration (Porges, 2011).

Correlation was stronger between the first and second factors which may suggest a bidirectional link between the feeling of being accepted within a group and compassion (Liu, 2017). We found a gender difference on the Body Sensations subscale but not on the other two subscales with males scoring significantly lower. Body awareness has also shown to be impacted by age (Cabrera et al., 2018) and psychopathology (Bernatova & Svetlak, 2017), which may be considered in further evaluative efforts.

In the third phase the NPSS was evaluated with CFA. The three-factor structure showed adequate fit, and the scale showed good reliability. In both phase two and three, scores distribution was leptokurtic and negatively skewed. This ceiling effect observed is attributed to sampling from the convenience general population sample and participants being prompt to ‘think about a recent specific situation when you felt safe’ which may have led to participants responding about a situation when they felt optimally safe.

Applicability of the NPSS may be improved by inquiring about a specific situation or event, for example, ‘please rate the follow-ing statements in relation to [insert your event].’ However, the original wording may be useful when determining the baseline safety is desirable, for example when the objective is mental health recovery (Lewis et al., 2019). The applicability of the NPSS could also be increased by formalizing a procedure for scoring and inter-preting subscale measures, as the bodily sensations subscale may be more useful in gauging feelings of safety in asocial situations. Though the NPSS is a relatively brief instrument, future studies are needed to explore whether a shorter form may be developed to expand clinical utility for cases in which rapid measurement is a priority.

This study has several limitations and suggestions for future work. First, since participants self-selected through convenience sampling rather than being randomly selected, they may have had stronger feelings about psychological safety than those in the larger population in general. While recruiting participants through social media has many advantages, it also has its potential biases, that may limit generalizability (Benedict et al., 2019). Future directions aim to understand more about the latent factors underly-ing the dimensions of the NPSS via CFA and once understood, will explore the possibility of creating a briefer measure. We are also collaborating with colleagues in clinical practice, who are engaged in trauma practices, to test the feasibility of using the NPSS in intervention planning and goal setting with service users. Further, future work could explore the psychometric properties and feasibility of the NPSS in more diverse populations and across a range of sociocultural contexts. While the difference in neuro-physiological expression of safety has insofar not been addressed by researchers, cultural differences in perception of safety and risk-taking have been identified (Liao, 2015). Exploring psycho-logical safety within dyadic relationships and mapping these using social network methods will allow for an improved understanding of how individual level factors can be considered with relation-ships and social structures that shape outcomes (Roussin et al., 2016). Future research should consider the impact of social net-works, systemic factors and cultural contexts and their impact on psychological safety within therapeutic contexts (Ash et al., 2021). The NPSS is a new and novel measure of psychological safety which integrates psychological, relational and physiological com-ponents of safety and has applicability across a range of health and social care contexts. The NPSS may shape new approaches to evaluating trauma treatments (e.g., compassion focused therapy) as well as broader relational issues and mental health concerns. For example, using the NPSS to better understand shifts in the window of tolerance of autonomic arousal (Porges, 2011) coupled with further work capturing narratives of what it means to be psy-chologically safe for clients who have experienced trauma. Research to establish the convergent, discriminant and concurrent validity of the NPSS and to explore its use with diverse commu-nity and clinical populations is underway.