Safe and Sound Protocol: A practical application of Polyvagal Theory using music

Dr Stephen Porges is – as well as our official Ambassador – the creator of the Polyvagal Theory. His theory proposes that the evolution of the mammalian autonomic nervous system provides the neurophysiological substrates for adaptive behavioral strategies. The theory highlights the role of the vagus nerve in emotional regulation, social connection and fear response.

Dr Porges went on to develop the Safe and Sound Protocol ™ (SSP), a music-based intervention used by therapists to improve social engagement, language processing, and state regulation, as well as to reduce hearing sensitivities.

How our nervous system connects us to the world

The mammalian nervous system branches first into our Central Nervous System (CNS) and our Peripheral Nervous System (PNS).

The CNS consists of the brain and the spinal cord. The PNS consists of the nerves which connect the brain and spinal cord to the rest of the body. The PNS is made up of the somatic and the autonomic nervous system.

The somatic nervous system consists of nerves that go to the skin and muscles and is involved in voluntary actions in the body. The autonomic nervous system connects the CNS to the visceral organs such as the heart, stomach, and intestines and it mediates involuntary activities such as breathing, heart rate, digestion and salivation.

How the autonomic nervous system connects to our sense of safety

The autonomic nervous system is made up of our sympathetic nervous system, which is used for mobilisation (think “gas pedal/accelerator”) and our parasympathetic nervous system, associated with rest and downregulation (think “brake”).

Polyvagal theory identifies a third type of nervous system response – the social engagement system (SES). Humans are designed to scan their environment continuously for signs of both danger and safety. Polyvagal theory describes this as “neuroception” and asserts that the SES is how humans seek and receive signals of safety.

The role of the vagus nerve in social engagement and safety

The vagus nerve, or tenth cranial nerve (CN X) is our largest autonomic nervous system nerve and interfaces with parasympathetic control of the heart, lungs and digestive tract. We can think of it as a ‘surveillance system’ for the brain, with 20% of its fibres carrying information from the brain to the body, and 80% communicating from the body to the brain.

The vagus nerve divides into the ventral vagus nerve and the dorsal vagus nerve. The ventral vagus nerve responds to cues of safety, influencing cranial nerves that regulate social engagement through facial expression and vocalisation. A ventral vagal state is characterised by social connection and feelings of safety. In other words, hearing voices and seeing facial expressions we believe to be loving or friendly creates a felt sense of safety in the body.

A dorsal vagal state is the most primitive and survival state of the human condition. The dorsal vagus nerve responds to cues of danger with immobilisation or what is often referred to as a “freeze” response. It is associated with threat which is (or perceived to be) overwhelming or inescapable.

Trauma creates a bias in the nervous system

Dr Porges says: “Trauma compromises our ability to engage with others by replacing patterns of connection with patterns of protection.”

Trauma can create a bias in the nervous system, or an unhappy ‘home away from home’. Encouraging a repatterning of the nervous system can help people to redress this bias and ‘come home’ to themselves. SSP is designed to do this by using music to engage the SES.

How and why sound can bring us back to safety

The system uses ordinary music including classical pieces and pop songs, as well as child-appropriate music such as Disney songs. An algorithm is applied to the music to emphasise the middle range of the music. This embodies safety by mimicking the sound frequencies of the human voice – one of our key auditory cues of safety.

In a defensive or dorsal vagal state, the stapedius muscle in the middle ear is inactive. This prevents it from doing its job – protecting the ear from damage by dampening movement within the ear in response to unsafe levels of sound.

Loud noise is a key indicator of danger or alarm. An ear with less protection from sound will result in greater sensitivity to sound, and a nervous system receiving danger signals from everyday sounds and noises.

How the Safe and Sound Protocol ™ is delivered

- Five hours of music

- Frequency and duration of sessions adapted to client needs

- Can be completed in-person, remotely or independently

- Average completion time of 10 – 60 days

The client listens to the specially filtered music via headphones, with sessions calibrated by their therapist/support professional. As a shift in nervous system state is the desired goal, the co-regulation offered by professional support is considered central to this modality.

However, the therapy itself can be experienced remotely, or listening can be done independently, with the client’s compliance with the programme monitored via an online dashboard.

It can be delivered by a range of professionals, including but not limited to:

- Psychotherapists and counsellors

- Physicians and nurse practitioners

- Social workers

- Occupational therapists and physical therapists

- Psychologists and psychiatrists

It can integrate well with other therapies, including but not limited to:

- EMDR

- CBT/DBT

- Internal Family Systems (IFS)

- Play therapy

- Neurofeedback

- Somatic experiencing

- Behavioural therapy

It can enhance treatment or support for the following:

- Trauma and PTSD

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Eating disorders

- Addictions

- ADHD

- Autism

- Sensory processing disorder

The science of Safe and Sound Protocol ™ (SSP)

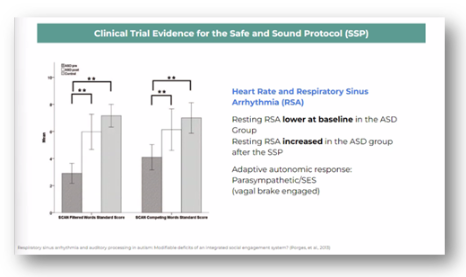

In Respiratory sinus arrhythmia and auditory processing in autism: Modifiable deficits of an integrated social engagement system? (Porges, et al, 2013) Dr Porges tested an intervention that stimulated the SES. Auditory processing improved and RSA increased in ASD following intervention.

Developing research

Below are some currently ongoing studies if you wish to explore the research further.

McCartan Early Intervention Study

- Efficacy study on SSP for low-SES children and infants

SSP Singing Study

- Comparing singing with SSP for adults with Parkinson’s Disease

Spencer Psychology Trauma Study

- Experimental study comparing SSP to treatment as usual for adults with PTSD

Children’s Hospital EDS Study

- Comparing SSP to unfiltered music for adults with Ehlers Danlos Syndrome

Children’s Therapy of Woodinville Medication Study

- Study on SSP and medication use in children with neurodevelopmental differences